“Mr. Munro,” the receptionist says, startling me out of my mental preparation. “He’s ready for you.”

I stand up and follow her into a large office. It’s game time.

It’s December 22, 1998, and I’m interviewing for my first post-Navy job. It’s for a leadership coach position at a firm called Right Management Associates. I applied for it a few weeks ago after hearing about it on the job hotline for the American Society for Training and Development (ASTD). Ever since deciding about 18 months ago that I wanted to pursue my own management consulting career, I’ve been active in the ASTD. It’s been good for networking, and I already have a hot lead for a training manager job with Car Toys in Seattle.

That doesn’t matter, though. My family has already relocated to West Tennessee since my wife has orders to the base in Millington. I must find a job there. In fact, she’s already been gone a few months. My command, in one last opportunity to bite me on the ass, has held up my early retirement papers until I agree to extend my service a few more months to help them get through an I.G. inspection. It means my family is gone, but the thought of a small pension for life is enough to make the sacrifice.

I’m well-prepared for my first job interview. The Navy offers a course called Transition Assistance Preparation (TAP)—everything in the Navy has an acronym. The instructor is a contractor with a ton of HR experience. He deviates from the outdated course materials and gives us a real-world look at what we’re getting ourselves into. In an ironic twist, I would later teach TAP for a rewarding four years in the mid-2000s. We were still using that outdated curriculum.

I take the course seriously. Most others do not. We’re instructed to wear civilian clothes. I love this—I’m so tired of wearing a uniform. So, I dress nicely. I’m the only one. Most are in jeans and T-shirts. One guy nurses a full-strength two-liter bottle of Coca-Cola each day for all three days, monkey-lipping it right out of the bottle.

I take full advantage. At each break, I speak with the instructor. He is who I want to be. I get his contact information. He’s a potential connection.

After TAP ends, I go to JC Penney and buy a dark blue suit. It takes about a week to have it tailored, but now I’m ready. Then I get the lead from Right Management Associates.

The ad says the leadership coach position requires a master’s degree (check), five years of experience (nope), and a list of other qualifications—most of which I don’t meet. It doesn’t matter, though. I’m prepared.

The ad mentions the use of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) in the role, so I buy a book, Please Understand Me, and read all about it. I take the assessment in the book and identify as Myers-Briggs type INFP. When I read the description, it sounds just like me. I should have taken that more seriously—it was the universe’s attempt to get my attention way back then.

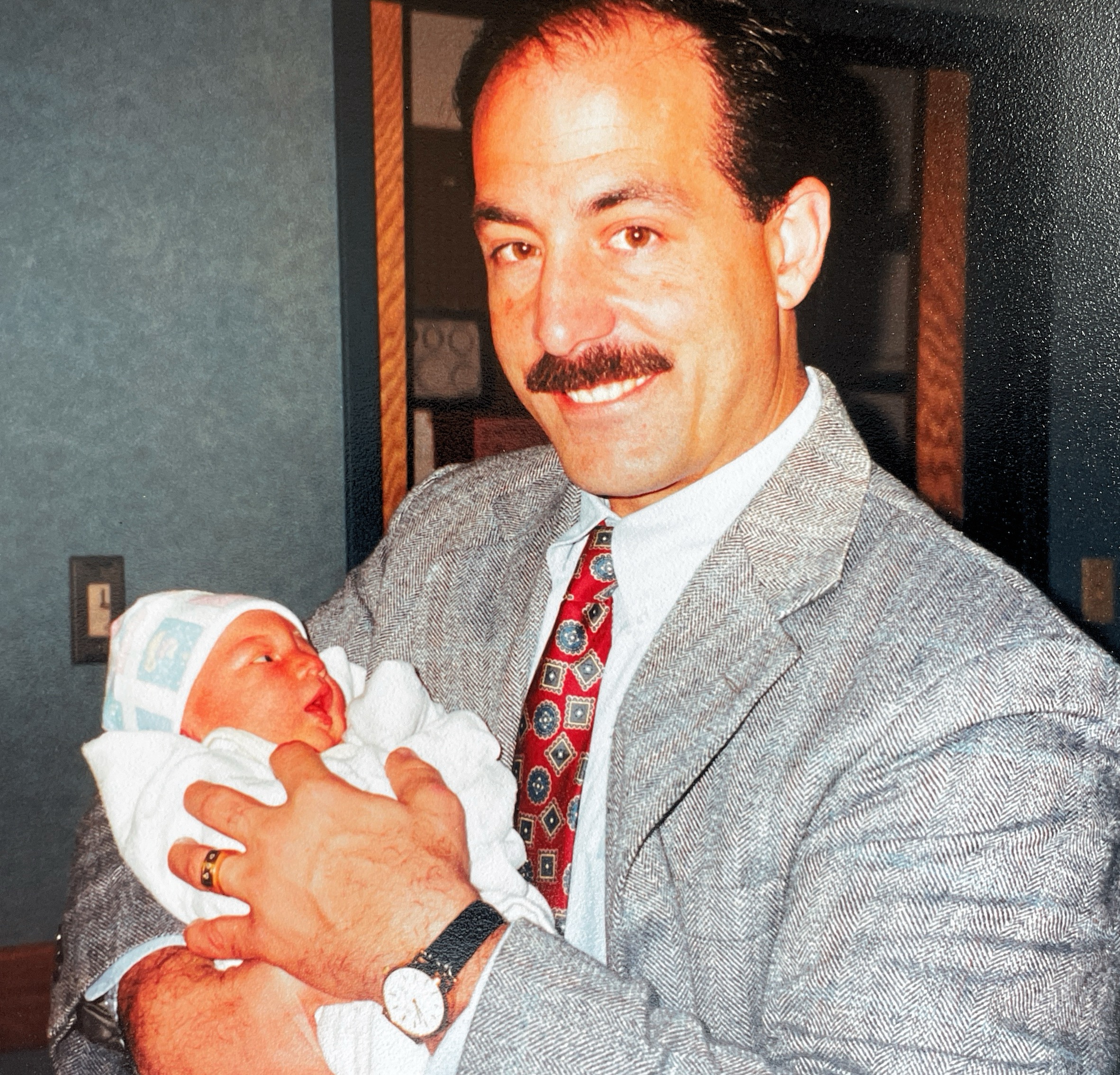

I take two weeks of leave to spend the holidays with Barb, Dustin, and her family. Then, a few days before Christmas, this interview is scheduled.

Barb drives me to the location and waits in the car. It’s cold outside, but I’m sweating nervously in my new suit. I’ve let my hair grow out longer—just barely within military standards—but I can’t afford to look like I’m still in the Navy.

As I enter the room, the hiring manager, the firm’s GM, greets me with a handshake. I deliver the proper handshake TAP coached us on, and he motions for me to sit across from him at a small round table.

I don’t remember much except that I absolutely nail every question. There are no scenarios I’m unprepared for. About half of what I say is true; the rest is pure exaggeration. I don’t feel a bit bad about this. The Navy has spent 15 years torturing me—I deserve this. I can do this. I have supreme confidence in my knowledge.

After the final question, he asks if I have any questions for him. I inquire about preparation and training. He assures me they will provide all the training I need, including for the MBTI. I’m excited. I can’t wait to get started. Of course, I have yet to be offered the job.

And then, he hits me with a reality check.

“Malcolm,” he says, “you interviewed great, and I’m confident you can do the job. Here is my problem with you: you have no gray hair.”

I’m floored. In my Navy world, at the ripe old age of 34, I’m one of the “old guys.” The oldest active-duty person in my life is probably my Executive Officer, and he might be 50. Now THAT’S old!

He continues.

“In this role, you’ll be coaching executives who have decades of experience and bad habits. You are what stands between them keeping their position or being let go, often without any compensation. What credibility will you have?”

I’m speechless but manage to make up some nonsense about having fresh ideas. I know it’s not convincing. He’s absolutely correct, and I realize I’m going to have to punch well above my weight for a while.

I don’t get that job, but I land another as a Supervisory Development Specialist at U.T. Medical Group. I fake my way into that one, too, but excel at it until Barb has to relocate a year later to the Washington, D.C., area.

When I start my business in early 2005, I find myself usually the youngest person in the room. My workshop audiences are all older, which makes sense since these are seasoned professionals. I survive by ingesting as much knowledge as I possibly can. I re-read all of my textbooks and feed myself a steady diet of the latest management, organizational development, and training books, seminars, and articles. I can master the room because, in this one area, I have a lot of knowledge.

Over the years, though, I’ve noticed a trend. I’m now often the oldest one in the room. And it’s no longer about gray hair—I have no hair. What I have are wrinkles and lines. And a shit-ton of experience to complement them.

I’ve learned that theory is absolutely useless in real-world environments. In the early days, I would use theory to predict what might happen. Now, I use my experience to demonstrate how most management theory is not worth the paper it’s printed on. I’ve learned that trying to connect to a deviant employee’s heart to help them develop a personal vision and channel that into their job to create meaningful work is absolute bullshit. Some people need to be fired.

The only thing that matters is experience. Knowledge opens the door, but experience wins the day. The one thing I’m complimented most on in post-workshop evaluations is my storytelling. I’m not surprised. Stories communicate in a way that a PowerPoint slide cannot hope to do. Stories share an experience. And a story tells you what predictably can happen rather than speculate on what might happen.

The one thing I’m always criticized for in post-workshop evaluations is my use of profanity. Here’s how I feel about that: I don’t give a shit. If you want me to give you a workshop that will provide practical advice on what works and what doesn’t, it requires some emphasis. Besides, the world of management is a tough one. If you want to succeed, gear up. Profanity gives the emphasis.

The final piece of the equation is wisdom. Wisdom comes from the lines and wrinkles. From the 35 weeks a year of travel to deliver workshops in 24 of the 50 states and in eight different foreign countries. After 20+ years, I can’t say I’ve seen it all, but I’ve seen a lot.

Over the past holiday, my son’s partner, Crystal, asked how much I charged for a one-day workshop. When I told her, she was shocked. She told me her college (UNLV, where she is finishing her Ph.D.) offered programs a lot cheaper.

Then I told her the reason. At UNLV, you get a professor of theory—a practitioner who is a career academic. Anything you learn is pure speculation. My programs are expensive because you’re paying for 20 years of real-life, no-bullshit experience from the trenches, the pits, and the depths. Knowledge + Experience = Wisdom, which for me has led to a great, lucrative career.

What knowledge and experience do you have? Have you ever taken the time to evaluate it? You might be an expert and not even realize it!