“I’ll tell you a story you’ll never forget…. a story about you…. and your cigarette”

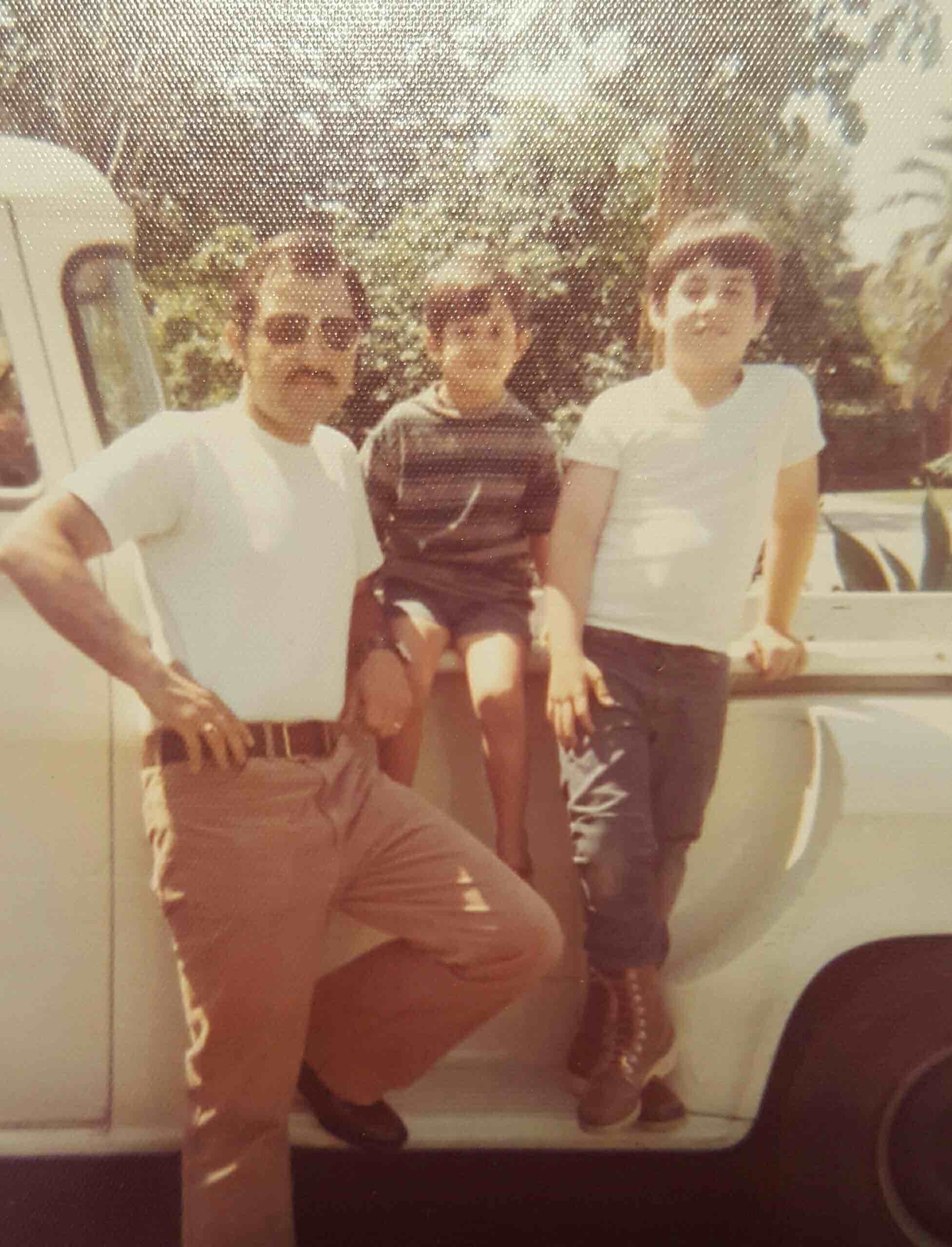

It’s 2008 and my daughter Allison, all of six years old, giggles uncontrollably as my dad sings that line as sort of a sea-shanty tune in ¾ time. I remember it well. He sang the same song for my brother Marshall and me when we were little. I’m glad Allison gets to experience this version of my dad. Papa, as he is known devotes all his attention to his grandkids. When the family is together, my brother Marshall and I often side-eye each other smirking as we remember the much harsher and moodier version of the man that raised us.

But my dad really has a cigarette story. A story I’ll never forget. Born in 1964 I grow up around cigarette smoke. Sometimes my parents both light up in the car, filling it with a cloud of acrid smoke. Our house is littered with ashtrays. More than half the butts have bright red lipstick on them. I smell it on my dad’s hands. Even when he washes them with Boraxo soap after working on his car. I still smell it today when I shake hands with a smoker. It rubs off and sticks to you. I smell my dad’s hands.

But as they say, the most critical non-smokers are former smokers. When my brother is an infant, my mom is changing his diaper when ashes from the cigarette dangling between her lips drops onto it, setting it on fire. From that moment on, a pack-a-day smoker turns into an anti-smoking, zealot, leaving dad in her crosshairs.

This also coincides with my parents’ conversion to Christianity. My earliest church memories are of a dark catholic church, sitting on rock hard wooden seats with the usher sticking what looked like a pool net on a long pole down the aisle so people could put cash in it. My Polish mom and Mexican/Scotch dad grew up as somewhat practicing Catholics. We go to Mass every weekend at Holy Family Church in Orange.

One day my mom is invited to a Christian Bible study group at McDonnell-Douglas, the company she works for. She comes home a different person. She converts my dad. In hindsight, I think he goes along only to appease her, but that soon changes. Much of the next few years is a blur.

They choose a Baptist church which is a pretty strict brand of the faith. While Catholics serve alcohol in church, some Baptists are aghast at the mere mention of it. Soon dad is dumping all his alcohol down the drain. One day I discover the short concrete tiki garden statue in the yard is busted into pieces. Mom says it was an idol, quoting one of the 10 Commandments, so dad destroys it. I guess it fell into the category of graven images.

But dad’s cigarette demons won’t let him go. The more my mom gives him shit, the more he resists quitting. He’s careful though to keep his habit from any of their church friends. This proves difficult when they do extended gatherings like beach parties or picnics. He seems ashamed of his double life.

Eventually we move to a different church closer to home. Since mom has us in church every time the doors open, dad puts his foot down and finds a church about 15 minutes away.

It’s a medium-sized, non-denominational church, Calvary Church of Santa Ana. On the first day we attend, Mom escorts me to the second-grade class, and I’m greeted by my soon-to-be best friend Brian Griset, who I know from school. I’m happy at Calvary. I attend all the way through the first couple of years of high school. My best friends are all made there. My parents make lifelong friends too.

They get involved. Soon, they are superintendents of the 2nd grade Sunday school class. They have leadership roles.

And dad is still hiding his smoking. And is quite ashamed of it.

As a management consultant by trade, I often look back at my life through that lense. Calvary was very much like a very traditional, old-school company. It was founded shortly before WWII with my friend Brian’s grandpa and dad, as some of the earliest members.

The current pastor at the time, Michael Samsvick, is only the fourth one in its history. Even though the format is exactly the same every week, we all get a bulletin with the service agenda when we walk in.

If you are a kid, your punishment if you screw up is having to go to “big church” with your parents.

“Big church” starts with the organ prelude. The scowling organist at the time reminds me of the one playing in the ballroom on the Haunted Mansion ride at Disneyland. Mom is pissed when I share that observation. Then we sing some hymns. The numbers of the hymns for that week are posted in black numbers on a small wooden shelf at the front of the church. An identical shelf is on the opposite wall. It shows last week’s attendance plus how much was collected in the offering plate. Pastor Samsvick does a long pastoral prayer, followed by the offering. We stand and sing the Doxology as the ushers walk down the aisle in columns of two carrying that morning’s haul. Then, the endless sermon. It’s likely only 25 minutes or so, but for me it seems an eternity. Then, mercifully, Pastor Samsvick says the magic words:

“Let us pray.”

That means it’s about over. After the prayer there’s an alter call with a song. Then, we are dismissed and Pastor Samsvick walks over to the side door, where you can say hello and shake his hand as you leave the sanctuary.

But sometimes, we have a special music performance. Maybe an instrumental hymn or a solo. And when it ends, there’s a palpable feeling of anxiety as we all instinctively want to applaud. But nobody wants to be first. In my recollection, I only heard applause on rare occasions. Nobody want to be the first one because there is an unwritten, unspoken, but completely understood rule that applause, “Amens, “praise the Lords,” speaking in tongues, or any sort of spiritual gyrations are absolutely forbidden. So, we applaud on the inside. But it’s very uncomfortable.

My dad still struggles to hide his smoking. The wider his circle of church friends becomes, the worse it gets.

And then, one Sunday night as the four of us are driving home from church, things change.

My dad is driving, and I’m in the seat behind him next to my brother. As we stop at the red light on 17th Street and Prospect, I look at the car next to us. And there he is.

Mr. Ash.

Mr. Ash from Calvary Church.

And Mr. Ash is smoking. A cigarette. I see the orange ash in the darkness. It’s only fitting a man named Ash is smoking, I guess.

Marshall and I yell loudly and point. Thankfully the windows are rolled up. I think seeing Mr. Ash producing ashes makes my dad feel a little better about his own smoking. From that point on, he makes less of an attempt to hide it. And maybe, from a spiritual standpoint maybe he figures God is also ok with it.

“After all,” he says, “I don’t smoke. The cigarettes do.”

By my junior year of high school, I’m now attending church with my future ex-wife who is into some strange Pentecostal stuff. But occasionally, I attend Calvary with my parents.

About that time, Pastor Samsvick passes away. Calvary is heartbroken. He is the last of the old school preachers who treats the flock like his own family. He’d visit sick people in the hospital and shut-ins at the nursing homes. Plus, unlike preachers today, he would preach every single week, all year, and just took a few weeks off during the month of August.

The search for a new pastor begins. The plan is to have a series of pastor candidates go through some interviews and do a sample sermon on a Sunday morning.

First up is a guy named Dr. David Hocking. Most of the regulars knew him as a guest speaker who often speaks at the annual prophecy conference. He is tall, well-dressed, good-looking, has a gorgeous wife, and a few apparently well-heeled children. He’s a scholar but also a dynamic speaker. He brings his A-game, which for a guy who likely didn’t have a B-game, was unnecessary. They select him and cancel the search.

My parents are ecstatic. My dad loves reading about Bible prophecy and “Pastor Dave” as Pastor Hocking insists on being called, is an expert and wrote a lot of books. I think my mom has a crush on him. She insists they sit up near the front.

My dad continues to smoke despite my mom’s passive-aggressive digs. Especially when we we’re in family gatherings were others smoke freely. Finally, he responds sarcastically “Ok why don’t we talk about your diet?” That shuts her up.

Calvary is getting back to normal too. Slowly.

And that’s when I noticed the difference.

When Pastor Dave preaches, he lectures about 90 MPH, and you really need to flip around in your physical Bible to keep up with him.

And then when he reveals a key point, he sometimes throws out a rhetorical “Amen?” He expects an “Amen!”from the crowd in response.

There are a few brave respondents at first. We all seem to feel that same discomfort we did in the old days after an applause-worthy solo. Most of the congregation, although they love Pastor Dave’s preaching, still feel chained to the old culture.

As time goes on, as any new CEO or company owner does, Pastor Dave brings in his own people. The sinister-looking organist is replaced by a stranger. The music director is new too. He’s well-dressed guy with a short, neatly trimmed black beard and a polished, baritone voice. They have an orchestra plus a piano going. The music, for church music anyway, is ON!

I join the Navy in 1983 and get stationed overseas. Calvary grows rapidly. Now everybody claps and says “Amen.” The culture is changing. Soon they make plans for a new building. The old parking lots we’d play kickball on during Wednesday night Boys Brigade meetings are dug up and a huge sanctuary is built. The old “big church” building becomes the Samsvick Memorial Chapel. My future ex-wife and I are married in it in 1985.

Calvary grows in size and scope. The new sanctuary is packed for multiple services. There is a lot of energy. But it’s very different from the church I grew up in.

Eventually Pastor Dave moves on and a lot of the old members, including my parents leave Calvary. I always wonder what things are like. I hear that attendance dropped significantly.

Then, in 2008, shortly after my dad tells Allison a story she’ll never forget, you know that story about him and his cigarette? I’m in Orange County on business and have an afternoon to kill.

I stop by my grandparent’s old house in Tustin where I spent so many years before and after school. Then I visit their current home at Fairhaven Memorial Cemetery in Orange, where they are buried not far from Pastor Samsvick. My close friend Brian Griset is buried there too. He passed away in 2010.

I stop by the house in Santa Ana I grew up in. The one with the lipstick-covered-cigarette-butt-filled ashtrays. It all looks the same and different at the same time. But there is one more place I need to see.

1010 N. Tustin Avenue.

The parking lot is empty, so I park near the main door of the big sanctuary. The doors are open, and I walk in. Most of the seats are roped off. Pastor Dave would often have the entire congregation get out of one of those seats, turn around and then kneel while he prayed. The few times I went there in its heyday there was a Broadway-caliber orchestra and choir, and the place was packed out. It was so different than what I experienced growing up there. And in a strange twist, there were people smoking out in the parking lot. My dad was there a few years too early, I guess.

But today it’s different. It’s quiet. There is no energy. It’s quiet, but somehow not peaceful. At least not for me.

Now, where I really want to go.

I walk across the courtyard, past the pay phone we would call our parents on if we needed to be picked up. The little green space behind it with tall bushes and palm trees still stands. We would play “war” here when we were kids in between services and when our parents hung around too long talking to their friends. More than once I gave an Oscar-worthy performance of a dying German or Japanese soldier.

I’m heading to the Samsvick Memorial Chapel. I walk into the narthex (churches have their own architectural terminology), across the familiar stained maroon carpet, past the polished oak banister that guides you up the steps to the balcony. That’s the same balcony I often fancied launching a paper airplane from, seeing if I could land it on Pastor Samsvick’s pulpit. Right in the middle of one of his marathon sermons.

I open the door, and it all comes back. “Big church.” It seems much smaller now. It’s a little dingy and very dated. It’s dusty and seems to be forgotten, but it stands despite a major culture shift tornado that came and went. But in its wake is that old comforting vibe I felt growing up.

I see Pastor Samsvick putting his watch on the podium to keep time. I see the stern-faced ushers in dark suits, walking down the aisle as the congregation sings:

Praise God from whom all blessings flow, praise Him all creatures here below…

I hear the startling sound of that little golf pencil stored on the back of the pew, hitting the concrete floor where it bounces and rolls, drawing all heads in your direction. I feel that embarrassment when your stomach growls loudly if you’re in the 11:00 service.

It feels good. And even though I’m on a journey that will eventually lead me in a different direction from the faith I found here, I will always cherish this place. I still dream about it often today. And ironically, the last time I was here was this building was in 1985, when I got married. The divorce was so acrimonious that it made me leave California for good. I don’t realize this until I get back in the car. The memories and lessons from so many years here are not diminished by the carnage caused by that first marriage. I did not even think about that wedding. I’m grateful for that.

Epilogue

Today, it seems Calvary is thriving although nowhere close to its size during the Hocking years. It’s active in the local community too. I don’t know for certain since I’ve not been back, but it seems like a bit of the old Calvary has returned.

Despite my mom telling my dad he would die of lung cancer, he did not. It was cardiac arrest from sepsis from a UTI caused from him not drinking any water. Something that was complicated by his ALS diagnosis. I remind my mom of this each week when I see she’s finished maybe TWO small bottles of Fiji water in the past seven days.

“Stop nagging me,” she complains.

I tell this long story because it needs to be told. For me to clear some space out of my creative brain cloud drive. That space shrinks the older I get, and you can’t buy more. But a true “story” needs to show change. I was X and then Y happened and then I became Z. I think maybe for a start I’ll just pull some lessons out I learned. Hopefully you might benefit from them.

- Be Comfortable in Your Own Skin. Don’t seek the approval of others. Once my dad got over the perceived shame others would have for him, he felt better about himself. His confidence grew. Along with his risk for lung cancer.

- Beware of Comfort Though. Comfort is the step just before comfortable routines are established. It’s difficult to remember a time before this time. We are seeing the comfortable routine of remote work beginning to unravel. The longer you wait to make the change, the more painful the change will be for you. Calvary had a comfortable status quo until a change at the top moved them into a new direction.

- Change Acceptance and Subsequent Productivity Take Time. It was a long time between silence after a great performance and the raucous “Amens” that were quite common in the Hocking era. Don’t get frustrated. Just keep the people talking. That helps. Change happens. It’s the acceptance we can manage.

- If You Are an Influential Leader, Think Long Term. Calvary grew under the charismatic leader but shrank when he left. If people follow you, realize the decisions you make will also impact them. What happens when you decide to move on? Who will be affected?

- Honor and Embrace the Past. If you have a place that was important to you during a transformational time in your life, revisit it. Even though my visit back to Calvary was back in 2008, I still feel that sense of peace from a visit back there. I don’t feel the need to return. What place would you benefit from a revisit?

And if there is a heaven, I’m pretty sure my dad is up there. But when my mom gets there, she’ll need to look for him in the smoking section, likely burning one with Mr. Ash and I’m sure a host of other closet smokers from Calvary and beyond.